In his Master’s thesis, Jelle Goos (Tilburg University) demonstrates the untapped potential of the circular economy within the fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) industry. His supervisor Marjan Groen comments: “Jelle has drawn attention to important mechanisms that may help or hinder the circular transition. The story of circularity needs to be told from different perspectives, and this study highlights how corporate rhetoric and actions may well have the right intentions, but ultimately need to be reviewed in light of their real contribution to a circular economy.”

Goos has collected data on the circularity performance of five FMCG multinationals that are members of the Ellen Macarthur Circular 100 group: Danone, Unilever, Anheuser-Busch InBev, the Coca-Cola Company, and Heineken. He concludes that the application of the circular economy is partial at best, even within these companies that can be considered frontrunners of circularity in the FMCG industry. Therefore, several recommendations are provided to accelerate the circular transition, in speed and in scale, aiming to maximize the benefits for society at large and to simultaneously boost economic returns.

How to get from a line to a circle

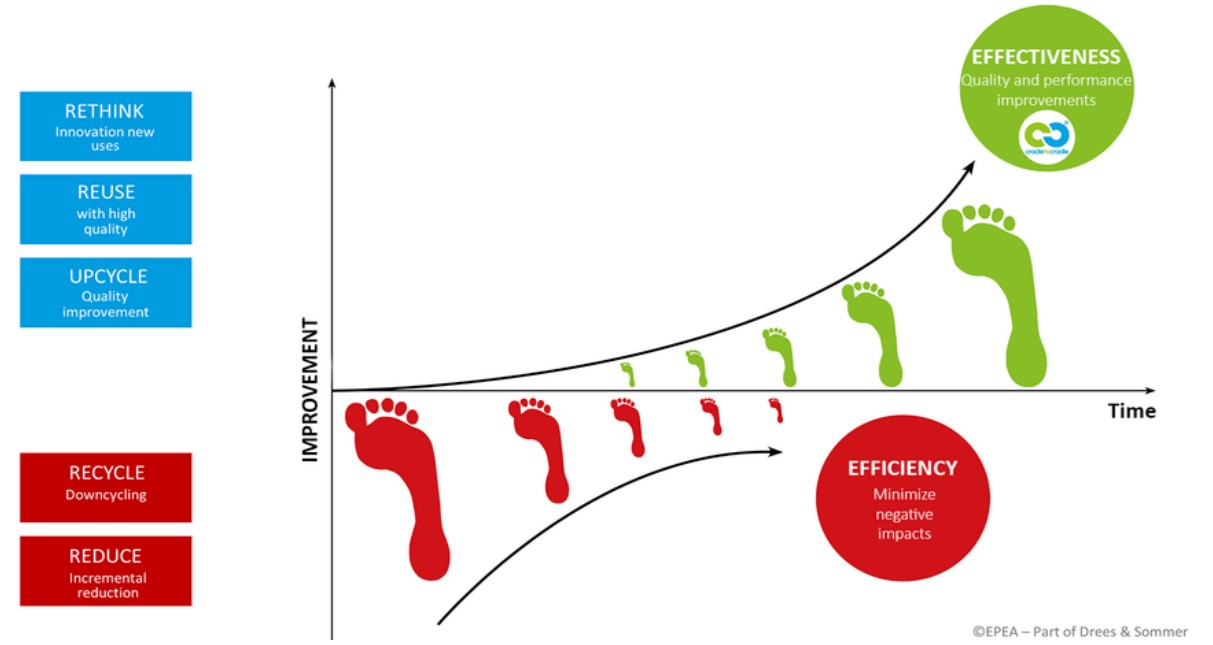

The results of the study show that corporate strategy and practices remain close to the linear way of doing business, with a focus on eco-efficiency (doing less harm) rather than eco-effectiveness (doing more good). Both concepts are illustrated in the figure below. Current business strategies and practices are aimed at improving the outcomes at the end of the pipeline, while the circular economy is more about redesigning the beginning of the pipeline.

(click to enlarge)

Moving from a straight line towards a circle sounds easy, but closing the loop requires a systematic rethinking of all business activities, which makes the transition complex. How can companies use resources rather than use them up? Goos´ study explores how multinationals in the FMCG industry are trying to move towards a circular economy.

Why is efficiency not enough?

Earlier research has highlighted important drivers for the circular transition such as resource depletion, stricter legislation, and changing consumer preferences. In this study, we saw that efficiency plays a vital role within the circular transition, because it creates significant cost savings while reducing the negative impact of businesses. Goos argues, however, that this is only a partial solution since 80 percent of the material value of FMCG goods is still wasted and never recovered every year. According to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, recovering part of this material waste, worth 2.6 trillion USD, is a huge opportunity for the FMCG sector. If companies want to capture a piece of the pie and become truly circular, then they should move beyond efficiency.

Rhetoric: What do FMCGs say about circularity in their annual publications?

The outcomes show that most companies mentioned triple-line growth, new business models, and technologies as the most important pillars of their circular strategies. The great majority of investments mentioned in the CSR reports were classified as recycling or reduction activities.

Action: What do FMCGs do?

Although more materials, packaging in particular, are recycled and a reduction in material usage has been achieved, these companies still design for the linear system, where recycling means downcycling, and no effort is made to reduce consumption. Goos argues that the circular economy is not about recycling and reduction, because operating more efficiently will not close material loops in the end. In other words, these companies are making the wrong things perfect and, as a result, they are doing perfectly wrong.

Criticism: How are circular policies perceived by external stakeholders?

The current way of doing business is mainly focused on ‘gaining more from less’ or ‘being more efficient’, rather than on becoming truly circular. This approach is broadly criticized by outsiders, because it focuses on eco-efficiency rather than eco-effectiveness, and it avoids hard choices that are required for realizing systemic change towards an economy that is restorative and regenerative by design.

Bringing it all together: What should these FMCG giants do?

The researcher concludes that continuing on the same basis as these FMCG companies currently do, reducing and recycling, will not lead to a circular transition. Rather than reducing inputs or delaying the cradle-to-grave flow of materials, FMCG giants are advised to switch towards a fundamentally different strategy. An example would be the ‘refuse’ strategy, which involves making the product redundant or offering the same functionality in a radically different way. These changes affect the heart of the business model.

Such strategies will enable FMCG companies to design out waste and pollution, keep materials in use, reintroduce biodiversity within agriculture, and rebuild natural capital. To speed up this systemic change, companies can switch towards circular business models, closing material loops, stimulating bottom-up innovation, and working with innovative start-ups, while keeping an overall focus on shared value.

Summarizing, the circular transition within FMCG requires smarter ways to manufacture and use products with the ultimate goal of becoming part of the solution, realizing sustainable growth and becoming more resilient.

Download the report: ‘Closing the loop for FMCG multinationals’ (pdf)